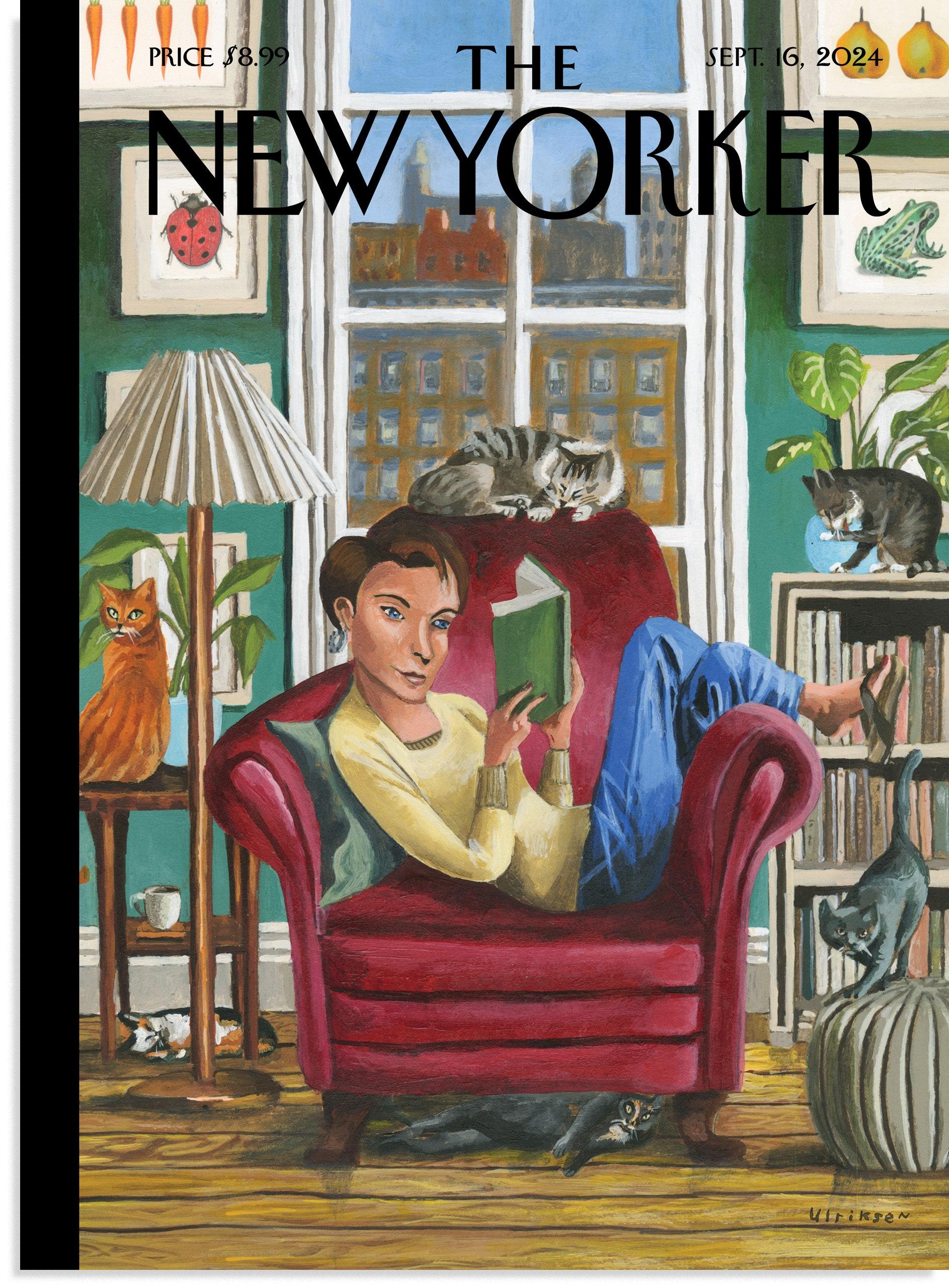

Forgive me for rabbiting on about “childless cat ladies”. But if The New Yorker won’t give up on it, why should I?

One feature of The New Yorker’s brilliance has always been its quirky covers - pointed social commentary through paintings. The September 16th cover depicts a young woman alone, lounging in a chair as she reads a book, surrounded by three cats. “I know so many single women who favor felines, including our eldest daughter,” says the artist in an editorial note. “And yet they all persist in being happy. Go figure.”

The cover is linked to an article by staff writer Margaret Talbot, “J. D. Vance and the Right’s Call to Have More Babies”. To be fair, Talbot doesn’t exploit Vance’s throw-away lines about “childless cat ladies” three years ago to call his character into question.

The cover is linked to an article by staff writer Margaret Talbot, “J. D. Vance and the Right’s Call to Have More Babies”. To be fair, Talbot doesn’t exploit Vance’s throw-away lines about “childless cat ladies” three years ago to call his character into question.

But she does link raising the birth rate to eugenics, fears about white replacement, and - you guessed it - Adolf. The reductio ad Hitlerum is alive and well at The New Yorker:

In Nazi Germany, the government instituted strict new penalties for abortion, and handed out medals to “genetically healthy” married mothers of “German blood”: bronze for four children, silver for six, and gold for eight. American eugenicists encouraged genetically “fitter” white families, the bigger, the better, with similar prizes. Putin is now offering a “Soviet heroine” medal for mothers with more than ten children.

Why have babies become a marker of political allegiance? More babies are needed = extreme right wing. Fewer babies are OK = the sensible centre.

Look at it this way. A baby is a unique human being, a life made for loving and being loved, a soul destined for eternity. As Hamlet says: “How noble in reason! how infinite in faculty! in form and moving how express and admirable! in action how like an angel! in apprehension how like a god! the beauty of the world! the paragon of animals!”

The more the better, say I.

You could call this sentimental bumph. Maybe it is. Dreams of a biggish family often collide with economic realities, household finances, medical issues, personal limitations and so on. But if people want to be happy, a life with babies is infinitely preferable to a life of empty leisure, languorous holidays, and middling job satisfaction. And cats.

Fundamentally, the fertility rate is not an economic issue, but an existential one. Life is a value in itself. For millennia, poets and parents have celebrated the blazing glory of being alive. We, however, have the misfortune to live in an age where philosophers can be feted for writing a book like Better Never to Have Been: The Harm of Coming into Existence. It’s bizarre.